When boxing was big and loud in Toronto

Toronto is a multicultural sports city. It is not just the city’s fans who speak to this multiculturalism but also the professional athletes who robe the city’s colours as they represent Torontonians. However, the city welcoming multicultural athletes is not of recent history. Toronto has accepted a diverse group of athletes for a long time, even before it identified itself as a multicultural city. During, one of Toronto’s most homogeneous states, the 1920s it was not hockey, baseball, soccer or basketball which were the first to welcome these athletes, but boxing. Before professional basketball, hockey and baseball promotions started signing foreign athletes, professional boxing during the 1920s in Toronto was a multicultural hotbed. Throughout the late 1920s, Toronto became a centre of the 112-pound flyweight boxing category— during that time, matchmaker promoter Playfair Brown signed some of the most sensational flyweight boxers from around the world.

How was Flyweight boxing illustrated in the media? How did Toronto become a centre for Flyweight Boxing? Who was Playfair Brown? And how did the media portray the race of these international stars, and does it speak to the diversity of lack of diversity of early twentieth century Toronto?

Toronto as a centre of Flyweight boxing

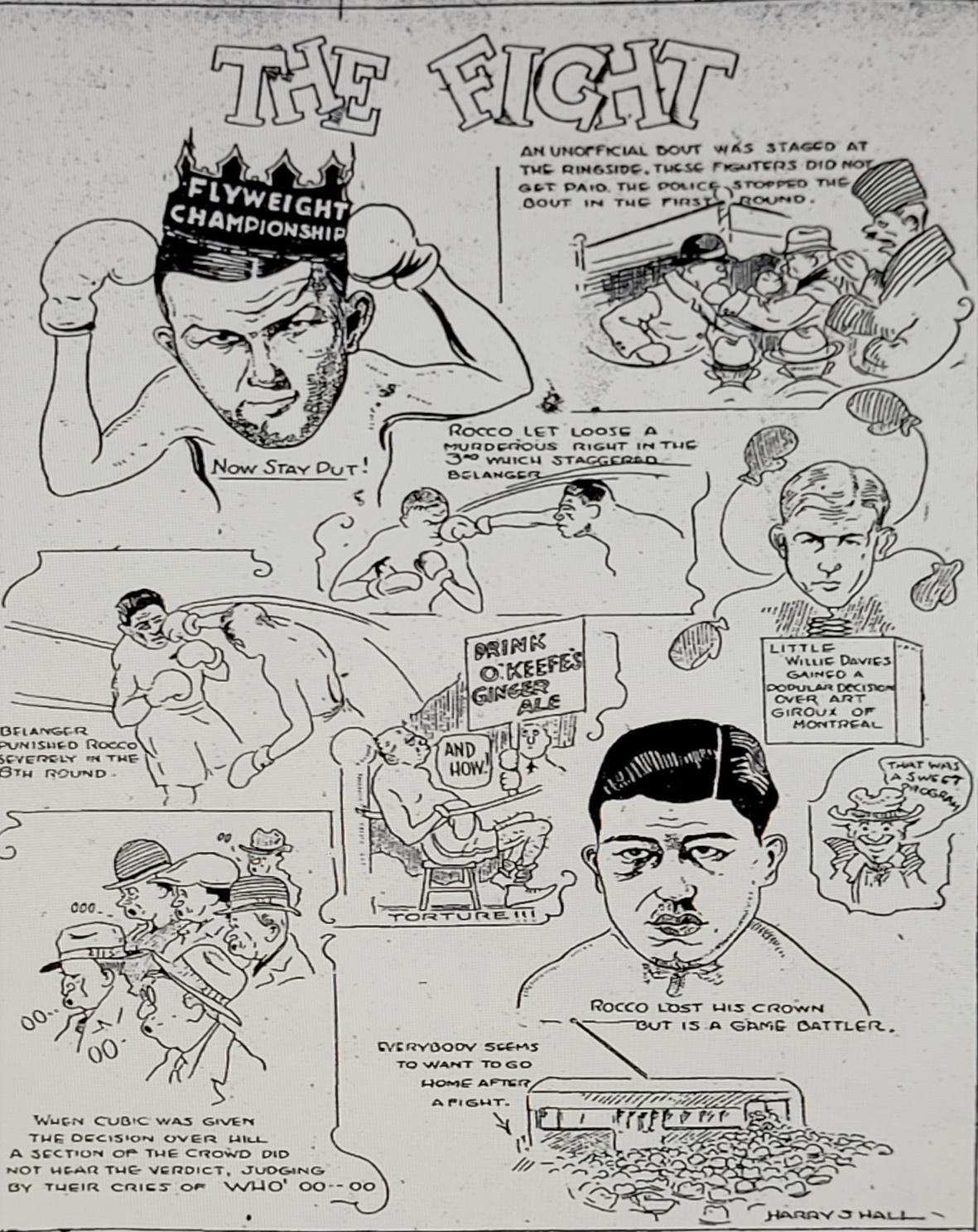

The flyweight division was new to boxing during the turn of the century. The famed and controversial sports journalist Lou Marsh called it “the greatest flyweight fight town in the world.” The success of Canadian fighters Frenchy Belanger and Steve Rocco lent itself to Toronto’s whirlwind of success. It was Belanger’s 1928 crowning as flyweight champion of the world, although stripped, which “made Toronto a flyweight oasis to watch the “midgets of fustiana.” The Daily Star, a Toronto newspaper, promoted the city as “the mecca of the mites of pugilism.” The previous quotes are examples of how the media described fighters’ physical size. Fighters were often depicted by their nationality and stature. For example, Ernie Jarvis was the “hard-battling and colourful English shrimp.” Lou Marsh called Eugene Huat was a “little French man” or a “Little Frog.” Another example, Elky Clarke was a “little Scotsman” and Alex Burlie was a “little Jewish Wolverine.” Willie Davis was a “tiny Welshman,” and Belanger was a “little Canuck.”

The Careful Watch of Playfair Brown

Toronto’s rise as a centre for flyweight boxing was under the watch of Toronto’s head matchmaker Playfair Brown. Brown arose from the fight scene sometime after 1918 when he became involved in a local gym called the Shamrock Athletic Club. Brown was a portly “easy going man” who would make Toronto a centre of flyweight boxing in the late 1920s. Brown arose from the fight scene out of nowhere. He was born in Victoria Harbor. At a young age, he moved to the small town of Midland, located on the Georgian Bay. Sometime early in his life, he moved to Toronto. After serving in the First World War and suffering shell shock, Brown would rise into the boxing scene. Brown’s motives to become a world-renowned promoter made Toronto boxing successful. He was a man who had his pockets in every card, even managing the great Black boxer Larry Gains. Playfair would travel across the globe, from England and Europe to the United States. He would have connections with both Jack Dempsey and Tex Richards. Over the next decade, Playfair signed some of the world’s greatest local and international 112-pounders, Frankie Genaro, Wee Willie Davis, Corporal Izzie Schwarts, Black Bill, Dark Cloud Ruby Bradley, and Ernie Jarvis.

Race

When it came to race, racism and or stereotyping, the media consistently noted Black and Filipino flyweights by their skin tone. Filipino boxers were called little brown” fighters. Black fighter “Black Bill” was a “picturesque little chunk of ebony.” “Dark Cloud” Bradley was a “coloured flyweight cyclone” and a “noir boy”. Marsh stated about Filipino fighter Young Dencio that: Folks who like to wager and are figuring on a little flier on the Burlie-Dencio main bout, do not want to figure this little Filipino as one of those running, swinging, little, Brown savages. This sunburned youth from the land of the hula-hula does not jump and swing. He crouches and bores in like a snowplough and he punches straight.

Here is an example of Marsh poking at Dencio while at the same time making note of the fighters boxing prowess. W.A. Hewitt writing about Dencio, stated, “the little tagalong Filipino, who is here, obtained his fighting name from Dencio Cabanela, the first Filipino boxer to really show class enough to hold his own with White fighters of reputation.” When Clever Sencio died in Milwaukee against Buddy Taylor, following a string of other Pilipino fighters’ deaths, the journalist wondered if “there was something in the tropical make-up to render them unable to follow the fast pace set by their white foemen of the roped arena.” Yet the writer stated that “none of the Filipinos gave an inch. But fought terrifically to the final bell.” The last example is in a cartoon of “Dark Cloud” Bradley, who is seen dancing and smiling like a minstrel manor, almost replicating one of the many racist tropes such as Uncle Tom or Sombo. The Cartoon states that “Dark Cloud Bradley was so pleased when he got the Decision, that he danced a Blackbottom for the crowd.”

During the nineteenth century, Toronto was not a multicultural city. For example, 81 percent of the inhabitants still in the 1930s were of British descent. It was a politically conservative city dominated by the protestant Orange Order. The strong protestant morals of the city are evident in the fact that in the same year, 1927, during Toronto’s limelight of boxing, the Temperance movement won, and the city passed a bill to illegalize alcohol. However, the development of pockets such as Kennington Market speaks to Toronto slowly evolving into an enclave for Jewish, German, Russian, Chinese and Black immigration, despite society still holding on to traditional racist, classist and ethnocentric tropes, which is evident in how the media emasculated immigrant, black and Filipino fighters. The press also promoted them, and the sport of boxing also compensated them handsomely. Professional sports allowed them to reach levels of success that were impossible in other places. Although the Daily Star satirized Bradley for being Black, this did not mean he could not fight for the flyweight title. Kid Chocolate, a Black fighter from Cuba, went from earning $60 a fight to $7,700. The same article stated, “the yardstick of a boxer’s popularity is not measured in terms of money when the fans want to see that boxer in action.”

The early success of immigrant fighters in Toronto speaks not so much to the demographical diversity but to society wanting to see the best fighter compete. It’s hard to say what were the motives of the Toronto newspapers. For example, Lou Marsh’s writings are a good example of carnivalization literature. How Marsh sometimes went about depicting flyweight boxers is in the title itself— “Slams and Salves,” “Knocks and Boosts” — Marsh determined the positive and negative attributes of these fighters by selecting what to congratulate and what to “slam.” He reaffirmed 1920-30 White Protestant cultural standards of race, ethnicity and gender—while also allowing a platform for fighters to gain publicity (good or bad) and to profit off that advertising.